VINfakta - Helge Skansen |

VINfakta - Helge Skansen |

Det følgende er sakset fra hjemmesidene til vinfirmaet Kobrand i New York som har en del vinfakta:

South of Siena in the southernmost part of the Chianti zone is the medieval village of Montalcino. The commune named for it covers 60,000 acres defined on all sides by rivers: the Orcia to the south, the Asso to the east, and the Ombrone curving around the north and west. Vineyard areas within this rugged, hilly area attain heights of up to 1,900 feet above sea level, yet only a twelfth of the terrain is capable of supporting vineyards. Forests, table lands and olive groves occupy most of the area, and of the 5,000 acres suitable for viticulture, slightly less than half is planted to vineyards producing Brunello di Montalcino.

The name of the village of Montalcino is derived from the fact that the mountain was at one time covered with evergreen holm-oak trees; holm-oak in Latin is translated as ilex, plural ilicis, and the inhabitants were also called Ilcinesi; therefore, Montalcino, mons ilcinus, means "the mountain of the holm-oaks."

Montalcino was inhabited either by the Etruscans or by the Romans, and documents as well as ample archaeological evidence have been discovered in the area. Around the year 1000 the first hamlets grew up around the churches, abbeys and convents under the protectorate of the abbey of Sant'Antimo. Built in 1118, this oldest and most important abbey was constructed on the ruins of a preexisting church of the Carolingian period dating from 814. The establishment of Montalcino in its present form took place between 1200 and 1400; in 1462 Pope Pius II elevated it to the status of Città (city).

Between the eleventh and fourteenth centuries Montalcino alternated between brief periods of peace and frequent altercations with Siena. The era of free communes and the strategic position of the city endlessly obsessed not only Siena but also Florence. In 1260, after the historic battle of Montaperti, Florence ceded Montalcino to Siena. Thus began, for the entire fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, a long period of well-being throughout the region and its countryside which saw the construction of many farmhouses and case-torre (literally, "tower-houses").

In July of 1526, during a period when all of Italy was subject to invasion by the Spanish empire, Montalcino succeeded in repulsing the attack of the Florentine troops and the papal army in only two days. In 1553, the Florentine army, along with the Spanish army and German mercenary troops, attacked the city and after nearly three months of fighting abandoned the siege. Two years later, on 21 April 1555, the Medicis and the Spaniards set siege to Siena, strangling it to the point of surrender. The only free stronghold remaining was Montalcino, which received many exiled Sienese families and established the Republic of Siena in Montalcino; for four years it withstood the strongest army in the world. In 1559 Montalcino was ceded to Spain and afterward to the Medici dukes.

Brunello di Montalcino, as compared to its region of production, is quite young. Montalcino is believed to have produced wines since the 10th century, when the present walled city was first established after the Saracen raids. Until the 1500s, records indicate that most of the wine produced was a highly valued sweet white wine of the Muscat grape called Moscadello di Montalcino. Only with the rise of the Medicis in the mid-1500s does any red wine production appear to have taken place, perhaps as a result of the family's ancestral roots in Bordeaux. Until the mid-1800s, the wines of Montalcino, whether red or white, were produced from the traditional Tuscan Sangiovese, Canaiolo, Trebbiano and Malvasia varieties. In 1842, the name "Brunello" was mentioned in the writings of the priest Vincenzo Chiarini, who was likely the first to identify this precursor of the clone of Sangiovese named for the exceptionally deep, black-purple color of its berries.

At the time, problems of vinification, blending and ageworthiness besetting Montalcino's producers prompted a pharmacist from Pienza, Clemente Santi, to initiate research toward solving them. He planted the first vines of what would become the family estate, Il Greppo, with the local vine called Brunello. In 1865 Santi won the first award for a wine bearing the name Brunello di Montalcino, and his grandson Ferruccio, son of his daughter Caterina, and Jacopo Biondi, continued to pursue his work. Determined to develop a vine which could produce a pure varietal wine of superior quality, he succeeded, in 1870, in isolating from his own Sangiovese vines the strain of Sangiovese Grosso which became known as Brunello. The vine yielded a wine of power and elegance distinct from other Sangiovese wines. A producers consortium was eventually formed in 1967.

Montalcino's soils vary widely. The areas situated in the north and east are dominated by clay soils high in volcanic sandstone. The vineyard sites in the western third of the region lie on soils which are chalky, gravelly and marked by loose marl high in calcium over a clay subsoil which, on the western fringe, is mixed with sand or silt deposits. From its four borders, the zone rises to its highest point near the center, at Poggio Civitella, where the soils are more strongly marked by galestro. The warm Mediterranean climate is cooled by the region's altitude, allowing the intense luminosity to gradually ripen the grapes. Flowering occurs during the last ten days of May and the first ten of June. Harvest normally begins in late September to mid-October. Under D.O.C. law, 70 percent of the yield is permitted to produce wines labelled Brunello di Montalcino; a selection may further be made based on grape quality, particularly in off vintages, to be bottled as D.O.C. Rosso di Montalcino, aged one year and sold immediately thereafter; or entirely declassified as "vino da tavola." The average annual yield in the Montalcino zone under all designations is 30,000 hectolitres (330,000 cases) among roughly 80 registered properties.

On March 28th, 1966, Brunello di Montalcino became Italy's seventh wine to receive D.O.C. designation, and was granted D.O.C.G. status in 1980. Requirements restrict maximum yield to eight metric tons per hectare under specialized cultivation, or one third that yield in mixed cultivation; olive trees may not be uprooted to replant vines. Regulations prohibit any blending of wines except of those from the same vines from the prior harvest, which must be clearly stated on the label. Obstacles to entry to the Brunello market are very high for new growers, requiring five to six years to produce a viable harvest plus the minimum aging of four years; new plantings are prohibited under EEC regulations.

The delicate pink juice of the tiny, nearly black-skinned Brunello grape yields a dark, purple-red wine which is characterized by extraordinary concentration, elevated acidity and enormous tannic extract. The wine is typically closed and quite austere when young, often backward and unapproachable. Generally considered to be young at ten years in an average vintage, Brunello di Montalcino's proponents contend that the best vintages can easily surpass a century and still remain in their prime.

Det følgende er sakset fra hjemmesidene til vinfirmaet Italian Wine Merchants (kjempeutvalg i kvalitetsvin og fyldige omtaler) som også ligger i New York:

The Vineyards of Montalcino

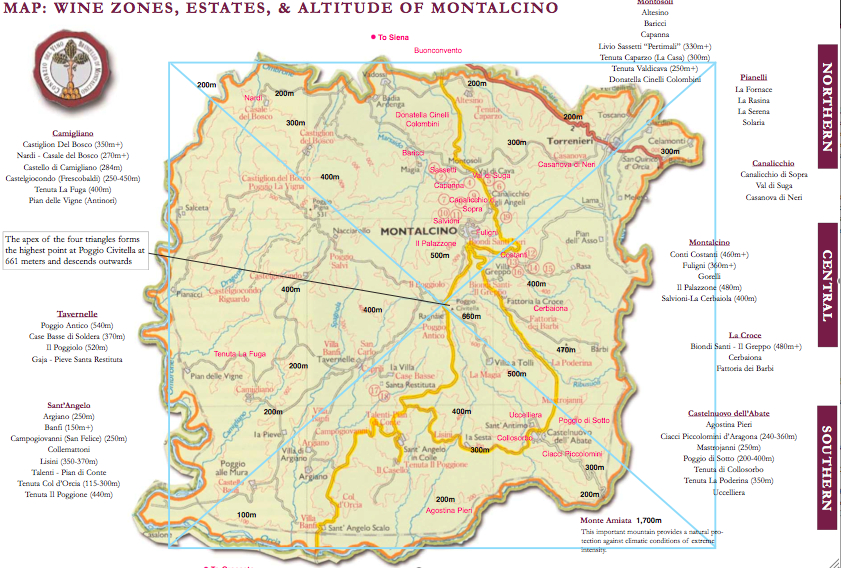

The Montalcino production zone can be broken into a range of subzones. Within each there are variations in altitude, soil composition, and weather patterns. In fact, there are nine subzones and the Consorzio lists more than 24 distinct microclimates in the area, which can confuse even the educated consumer. To make it more manageable we have divided the region into three territories—central, north, and south—that provide a general guide to Brunello styles.

The differences in altitude and exposition throughout the zone are a major factor in wine style since they play a substantial role in the vegetal cycle of the vines. Compared to the Chianti zone that is its neighbor to the north, Montalcino enjoys a predominantly Mediterranean climate as well as high altitudes that cool the grapes and help prevent disease. To understand the topography of the region, we recommend looking at Montalcino as an inverted cone with its peak just south of the town of Montalcino, which divides the square into four isosceles triangles with the center forming the apex of the cone). From the center, the slopes generally descend outward across the region.

Due to high altitudes, evening temperature drops and cooling winds sustain a slower cycle in vineyards like Il Greppo at Biondi Santi (480m+ above sea level) than is found in lower altitudes such as the southwestern site of Col d'Orcia (115-300m above sea level), where sandier soils and the lower elevation both promote a more advanced cycle. This variation is captured by juxtaposing these two wines from the same vintage: you will experience a denser, low acid, approachable wine in the Col d'Orcia, for instance, while the less developed Biondi Santi is marked by the structured tannins and high acidity that are ideal for longevity. Adding a third wine to the comparison enhances this hypothesis: Il Poggione (200-400m) combines the finesse of Biondi Santi and the approachability of Col d'Orcia. In fact, if you are looking for a balance between finesse and approachability, we recommend the elegant and structured wines of Il Poggione, Cerbaiona, and Poggio di Sotto, all of which are classically made Brunello.

High Altitude Delivers Wines of Structure

High Altitude Delivers Wines of Structure

Brunello begins around the hilltop town of Montalcino. This central subzone (also known as Montalcino), along with La Croce just below it and Tavernelle to the west, forms the traditional heartland of the Brunello di Montalcino DOCG. These are among the most elevated zones, where the altitudes (indicated next to certain estates on the map) provide the perfect habitat for more perfumed and elegant wines of structure and longevity, as do the southern and eastern exposure and the producers' vinification technique. These characteristics are enhanced in many of the top wines because producers intentionally balance ample but mature tannins with elevated acidity. The Tuscan treasures from the central area include the historic estates of Biondi-Santi (480m), Fattoria dei Barbi, Conti Costanti, and Fuligni as well as more recent efforts from Il Palazzone and Cerbaiona. Continuing toward Tavernelle, you find the classic Brunellos from Poggio Antico (540m), Case Basse di Soldera, Pieve Santa Restituta, and Il Poggiolo (520m).

Where Ripeness Meets Structure

North of the Montalcino subzone the high elevation of the central region begins to taper and form the northern territory, which is made up of Canalicchio, Pianelli, and Montosoli (and also includes the western area of Camigliano for this exercise). These subzones have a diminished share in the warm, dry Mediterranean climate and high altitude of their neighbors to the south, and the slight differences in temperature, humidity, and elevation breed wines of both ripeness and structure. The minimized exposure to cooling winds also contributes to the ripeness of wines from this area. This is epitomized by the wines of Capanna and Altesino's Montosoli cru, which typically combine serious aromas and elegance with power and fruit. Further west, the wine of Silvio Nardi expresses elegance and fruit with slightly less acidity places it among best values.

Approachability on the Lower Slopes

The southern region, like the others, features dramatic shifts in altitude from estate to estate. But the warmer climate shows through in all the wines. The vineyards that fan out eastward from Tavernelle into Sant'Angelo are exposed to a more unrestricted Mediterranean climate than the rest of Montalcino, with sandier soils, less wind, and lower altitude (similar to the more southerly exposed Maremma zone). The effects can also be seen in other crops: the olives from this region will turn black while olives found on Il Greppo are still green. And as with the olives, the climate contributes to a denser, less acidic, fruitier side of Brunello. The vineyards that spread west into Castelnuovo dell'Abate deliver similar characteristics. However, some estates, like Camigliano and Il Poggione (200-400m), have elevated vineyards with southern and western exposures that create potent wines with a spectacular combination of structure and ripeness.